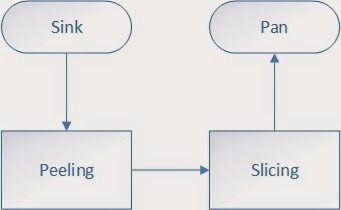

Raw material was a bag of beetroots, about 30 pieces. It will represent the supplier. Then there are two necessary working phases which add value to the customer. The beetroots need to be first peeled. Then they must be sliced into bits. Finally they go into the pan.

|

| Process Flowchart. |

The production plant could be set up in different ways. But in order to eliminate waste, everything should preferably be close to avoid unnecessary motion and transportation. With only two work phases there's not many places for inventories, but one possible place would be between peeling and slicing. If you first peel all the beetroots, you need to keep them somewhere before the slicing. But if you work in a one piece flow, you don't need any extra storage between the phases. Then there's also no over production, because one beetroot is always enough to enter the next work phase.

My factory had only one employee who needed to task switch between the phases. There was also some need to move. With two employees this could have been avoided. But unfortunately recruitment for housework is sometimes really hard.

|

| Factory setup: Sink, Work Phase 1, Work Phase 2, Pan. |

Keep things tidy and in order. When the equipment is on their places they are easy to find. Keeping your gear in good condition (knives sharp) makes your process more efficient. With tools fit for purpose, like my peeling knife, you can not fail. You can cut off just the skin and no valuable beetroot is lost. In lean this mistake-proofing is referred as Poka-yoke.

|

| Proper peeling knife. Poka-yoke. |

Fortunately the supplier had provided me with so good material that there were no defects. Quality control happened visually before the peeling phase.

Because the employees were both trained in continuous improvement and empowered to make changes to the plant layout, they came up with a slight process improvement after the first half of the work. The need for movement was decreased by moving the pan closer to the slicing place.

|

| Factory layout mark 2: More compact. |

When the materials ran out, the plant was simply shutdown. No capital was left in inventories. In the end, the customer received a pan full of sliced beetroots. As she had ordered.

|

| After shutdown and clean-up. |

In the text above I have tried to identify different types of waste and write them with italics. One could argue this wasn't a process, but a project. If the work would have continued, there would have been a need for a proper disposal of beetroot peelings. They were simply piled and thrown to garbage after the work was completed. But how to do this properly in a continuous process is left for the reader as homework . ;)